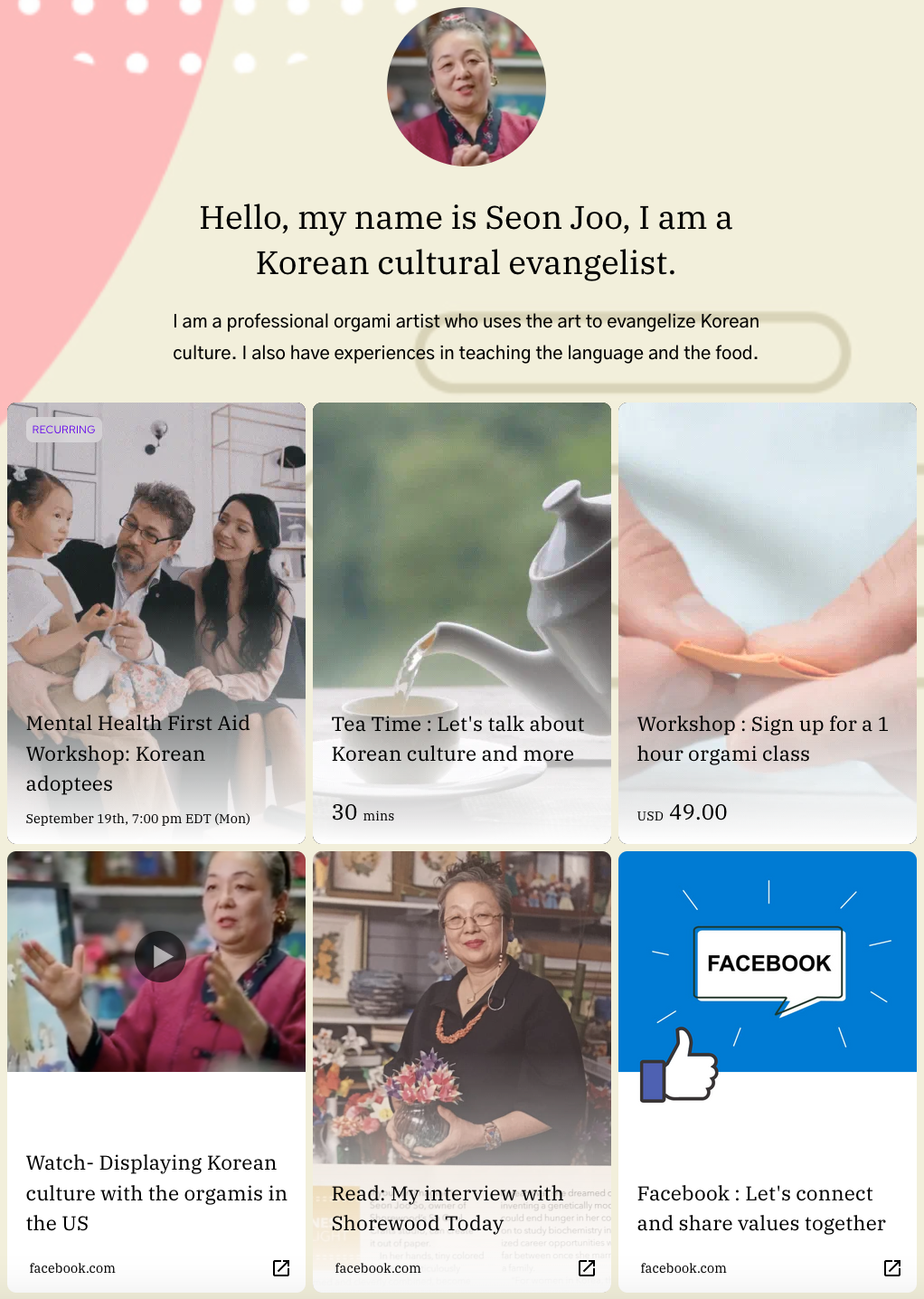

Origami expert Seonjoo So invites Korean adoptees to a mental health seminar

The total number of orphaned and abandoned children that South Korea has sent overseas into adoption is approximately 200,000 children, where three-quarters of those children were adopted by American families. Seonjoo So, the vice president of Korean Society has been helping these children and American families for many years. She served as a principal of Milwaukee Korean School, where they help adopted Korean children until 2019.

She is also an origami expert. In 1996, she started origami in Korea. She is an origami and paper winding instructor and does Hanji (Korean paper) crafts, Jiseung crafts and Hanji paintings. Jiseung crafts are made by cutting traditional Korean paper thinly and twisting double and single strings to make crafts.

Korean children are often adopted into the United States, and I heard that you are holding a workshop on the mental health of these adoptees and their parents in October. Please tell us more.

The Milwaukee Korean School holds an annual Lunar New Year celebration for Korean children. From 2006 to 2019, it has been 15 years since we invited families of adopted children to meet. The adopted children I met in 2006 are all grown up and have become college students or adults. Now, there are hardly any adopted children in Korea, so teenagers are the youngest group in the event. U.S. parents adopt children from Korea, and later they find that there is a big cultural difference. So they requested us to teach them about Korea, and we are holding various events to help them.

Adopted Korean children face different mental challenges. I’ve witnessed some examples. Some kids are not viewed by others as what they call American, many don't know Korean language, few have Korean friends, and K-culture doesn’t really mean much to them. There's inner conflict between like and hate emotion towards Korea. We have adoptive parents seeking help on how to help them.

I am hosting a mental health seminar in October on both Zoom and offline (the last session). The speaker of the mental health seminar for adopted children is Dr. Ok-Soon Jo, a professor of counseling at Moody Theological University. She has often given her education through online seminars. She runs the Korean U.S. people Mental Health Institute in Chicago. While learning online, I thought that it would be nice to meet face to face so that people can give a hug to each other. So, I prepared last week's seminar as an in-person class. I hope it will be a seminar where we can meet and share. My dream is to continue to be friends with Korean adopted children who attended seminars.

Who can benefit from this seminar?

Korean adoptees and adoptive parents are welcome to join the online Zoom seminar. If you think to yourself, “why do I not feel comfortable in the U.S.?” and feel it would be good to study about your own mental problems, the 1st and 2nd generation of immigrants from Korea to the U.S. are okay to come.

How many Korean adoptees are there in the US?

This June, we held a cultural camp in Wisconsin, and 200 adopted children and their families took part. Milwaukee is the largest city in Wisconsin. Most of the Koreans and adoptive families mostly live in suburbs. When we prepare a camp like this, the families of adopted children are scattered here and there, and they drive more than an hour to participate in the camp.

U.S. people seem to adopt a lot of children.

U.S. people take adoption very coolly. When they have the capacity, they adopt kids and raise the children with the utmost sincerity and love them as part of doing good deeds for the society. They also worry about the kids. “This child was born differently than me, and what if I don’t take good care of him/her?” One time, when asked why they adopted children, they said, “They made me a parent, and this is more than anything I did to my children. I thank them for calling me Mom and Dad, and I’m happy to be part of the family together.” I was moved by these words. The philanthropic spirit of these U.S. parents are amazing. When I complimented them, they humbly confess, “I don’t know how to raise kids and don’t do well.” They just say that they are happy to be with those children.

Koreans’ perception about adoption is so different. So I want to help as much as I can. What I learned as a principal of Milwaukee Korean School was being able to connect with the Korean government and receive funds. They provide funds for Korean adoptees who have been adopted abroad through the Overseas Adoption Agency. Thanks to this, I can ask the adopted children to have dinner together, make a lot of programs for them, and teach them Korean culture. It's nice to be able to collaborate because I'm on the bridge between Korea and the Korean adoptees living abroad.

I think there is a case where the mental problem of Korean adoptees became a problem.

Serious incidents of suicide or violence have been reported in the news. In our neighborhood, adopted children and their families often complain of anxiety and depression. As these adopted children grow up to be teenagers, they begin to see their own facial features in the mirror and begin to care about their appearance. Their peers sometimes make fun of their appearance and call them by nicknames based on the shape of their face, such as small eyes and a small nose. Then their parents say to their kids, "It doesn't matter. All people are different.”, but it’s no use. In this case, kids with strong personalities show off their power. Children who grew up in good families tend to give up their power rather than reveal their power and say, “They don’t let me in the group. The other kids don’t like me.” They become negative, and their parents feel sorry for them. From a young age, it is difficult for parents as well. They come to think that they have their limits in convincing children. This is something that parents can't do, so it's frustrating. If you look at the news, Asian people are killed with the ideas around “Asian Hate” and this worries Korean adoptees and their families. This prompted me to do a mental health seminar.

Seonjoo's Story as a Origami / Jongyijupgi expert

How does origami relate to Korean culture? From the word “origami”, I see that it’s coming from Japan.

I came to America in 2006 to study curriculum and pedagogy, and at that time, all U.S. people knew was origami. They saw me folding papers to make flowers and said that it looks like Japanese origami. At the time, I thought origami was something similar to Korean Jongyijupgi (종이접기) and I thought it was good that it’s so widespread. After studying origami, I learned that Japanese origami is to fold a single item out of a single sheet of paper, and you should not use scissors or glue. Japanese origami maniacs gather and hold annual competitions, greatly developing origami. Jongyijupgi in Korea can be done by anyone with hands, from kindergarteners to old people. There is no restriction on the use of glue or scissors in Korean Jongyijupgi.

In order to show Korean Jongyijupgi, I started to show how to make a swan by folding 500 and 300 sheets of paper. When they saw that 500 or 300 sheets were used to create a work, U.S. people began to admire the artwork and my patience on doing such a work. In 2012, SoCool Crafts Studio was launched to hold private lessons and lectures about Korea. U.S. people like to add programs to their birthday parties, and I am often invited to hold a program or decorate the event with papers. It has been 10 years since then, and the studio has become famous in this area. I also appeared on TV and in magazines. I am turning 60 in a few days, and I am weak in technology. It was great to be able to create a website with the help of David, the co-founder of Ceeya.

I like the Korean identity. The reason U.S. people don’t think highly of Koreans is because they don't speak English well. A public school is creating an after-school program that uses school space in the afternoon. I am invited there to teach Korean culture such as making paper flowers and paper dolls, cooking bibimbap, kimchi, and bulgogi. It's October, so we make a Korean traditional mask for a Halloween party.

Lastly, is there anything you would like to say to those who will attend the workshop?

“You’re not alone.” I want to say everyone has pain, and we need to find a way to get better and learn how to support each other with love. The motto of this mental health seminar is to get together and become friends.

I teach in other lectures, and I want to show that Korea has pursued cultural development to this extent by teaching Koreans through Jongyijupgi and crafts. Considering the global environment, I want to introduce Korean crafts to future generations. Other crafts involve buying new materials to make new things, but Korean crafts don't start with new materials. Our ancestors had already colored old books and made them into crafts using Korean paper. I want to help with environmental issues through this kind of recycling art. I want to reveal a hidden part of Korean culture.

Link to apply for 4-week mental seminar for Korean adoptees (Oct 6th - Oct 27th, 2022, application deadline: September 30th)

Writer: Eva Yoo (https://www.ceeya.io/at/evayoo)